Panel Recap | Wandering Plants: Horticulture, Colonialism, and Cross-Cultural Histories

This panel begins with Rubén Montesinos' visual research project, The Horticultural Guide, to explore the complex relationship between plant mobility and colonial history. Rubén's project examines features, forms, species, and other elements to reveal the mutability of horticulture in urban landscapes, highlighting its role as a tool for socio-cultural expression.

The discussion covers topics such as horticultural practices in Mexico City and their colonial connections, the global migration of crops like pineapples and its economic and cultural impacts, and how artists Minerva Cuevas and Ryan Villamael reflect on the relationship between plants and colonialism in their exhibitions. It also focuses on plant mobility and cultural fusion in the Americas, Southeast Asia, and China, with particular attention to the unique social relations formed by Chinese communities in Southeast Asian pineapple plantations.

Additionally, drawing on Gilles Clément's The Garden in Motion, the discussion will incorporate examples of productive landscapes in China to further explore the temporality and mobility of plants, showcasing the profound impact of horticulture within diverse historical contexts.

Lin Haodong: Welcome everyone to our panel discussion. I’m Lin Haodong, the director of Stasis Space. I’m delighted to have Hang Ping and Jiang Yao from Plant South Salesroom, as well as Zheming in Canada, join us for this session. This panel is based on our current exhibition, 园艺指南 A Guide on Gardening; therefore, before we start, let me introduce the exhibition.

This exhibition focuses on a horticultural project in Mexico by Spanish artist Rubén Montesionos. The project captures various oddly-shaped shrubs found on the streets of Mexico City. Using these shrubs as a starting point, the project explores not only the plants themselves but also the class-related aspects of Mexico City. For these reasons, we’ve invited Zhinan Shop and Zheming to participate in this discussion. To kick off, I’d like to share an image that serves as a starting point for our conversation.

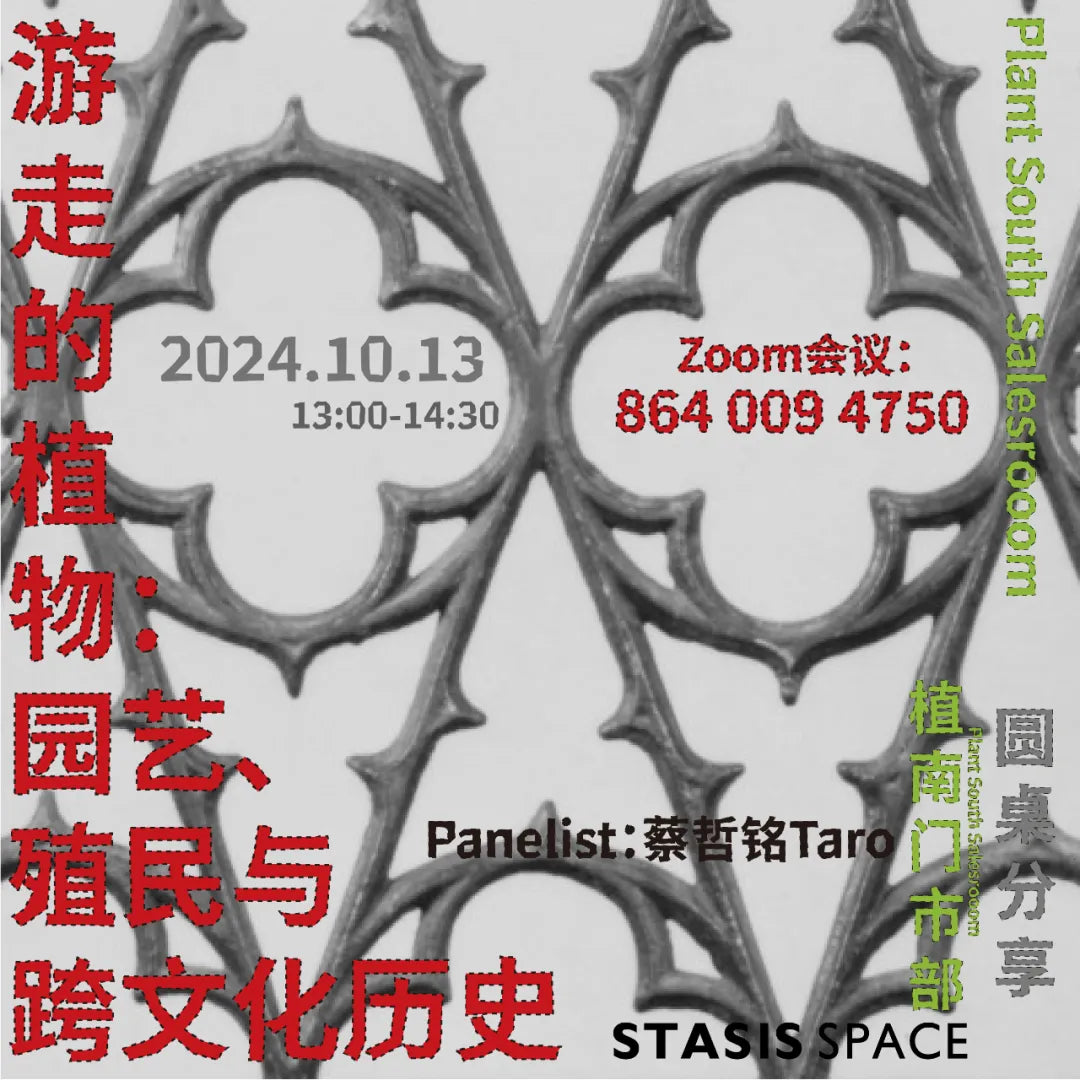

This image is something I stumbled upon while designing the exhibition poster. It depicts the wedding of Louis XV’s son, a masquerade ball with a cosplay theme. The participants dressed as all sorts of strange and interesting things. If you look closely, you’ll notice some dressed as Chinese or Turkish figures and even as shrubbery. This type of costume connects to the themes of our exhibition. For instance, some visitors have asked why these shrubs are trimmed into the shapes of cats and dogs. This image makes for a perfect introduction to today’s discussion.

Let me now invite Zheming to speak about horticulture in Mexico City.

Taro Zheming: The oddly shaped trimming styles you mentioned actually first appeared in Roman times, but they were revived in Europe during the 16th century, eventually becoming increasingly elaborate. Initially, the trimming styles were simple shapes like pyramids or spheres, but they evolved into highly extravagant designs, including spirals, animals, and even human figures. The film Edward Scissorhands depicts this concept beautifully, showing how Edward’s scissor hands are particularly adept at sculpting shapes, much like cutting hair. This style of pruning was extremely popular in Europe, becoming a form of cultural competition among European nations. It spread from France to the Netherlands and eventually to England, developing into distinctive styles in each country.

What fascinates me about A Guide on Gardening is its exploration of a Spanish photographer discovering these highly European pruning styles in Mexico. My background is in landscape design and garden history, so I often photograph similar phenomena on the streets. What’s intriguing about this book is its postcolonial lens, where a Spanish photographer revisits a phenomenon birthed under colonial influence.

One reason for the prevalence of this European gardening style in Mexico is the Spanish colonization that began in the 16th century. Throughout the colonial period up until independence, Spanish influence deeply shaped Mexican gardening, urban planning, and architecture. If you ever visit Mexico City, you’ll see many gardens with distinctly European styles, featuring meticulously trimmed hedges. In square-shaped plazas, you might find intricately sculpted shrubs anchoring each corner as focal points.

Pruning these shrubs is much like cutting hair; it requires regular maintenance to preserve their shape. This means significant time and financial investment to maintain, say, a cat-shaped bush. Without regular trimming, the shape deteriorates, and the design becomes unrecognizable. The more frequent and elaborate the pruning, the more it demonstrates a family’s wealth. To some extent, this became a subtle yet ostentatious way of flaunting one’s financial or social status—an understated form of wealth display.

When we talk about shrubs, we’re not just discussing plants but also their broader implications. With that in mind, I’d like to invite Zhinan Shop to share their perspective on the relationship between plants and colonization from a global historical lens, or any other related topics.

What truly resonates with me is not just the shrubs but the context behind them. I notice the scenes in the background, such as cracks in walls being overtaken by plants or shattered mirrors. These elements reflect something more specific and tangible about Mexico City itself.

Since Hang Ping often engages in artistic practices, could you share more about exhibitions or creations where plants serve as either the subject or the background? This might provide us with a better perspective for observation.

When Zheming and Jiang Yao were speaking earlier, I caught a detail about shrubs being trimmed into the shapes of cats or dogs, becoming symbols of wealth. In our work on The Wandering History of Pineapples, we discovered that pineapples could once be rented, transitioning into a stage of everyday life—a widespread and civilian-level phenomenon. At this stage, a shared societal consensus transformed the pineapple into a symbol of wealth or status.

This process shares a common characteristic: it strips away the original natural attributes of the object. For instance, when shrubs are pruned in a garden, they are shaped into forms that deviate from their natural growth. Similarly, during cultivation, actions are taken to make them better suited to urban environments. The same applies to pineapples. When we think of pineapples, we typically imagine how they appear in a fruit market, which is vastly different from how they look in a pineapple field. The original features—such as their leaves—are often excluded from our mental image. In our minds, we tend to retain the version that has been stripped of its so-called “natural attributes.”

I find this phenomenon quite fascinating. I’d like to elaborate by referencing two art exhibitions that respond to the colonial theme and explore the transformation of natural objects into artificial ones through processes like pruning.

Hangping: This exhibition was presented by Silverlens Gallery, which has spaces in both Manila and New York. The artist featured is Villamael Ryan, whose primary medium is paper cutting. The exhibition text was written by the chief editor of the University of the Philippines Press. The title of the exhibition is Return, My Gracious Hour, and it draws inspiration from Jose Rizal’s poem Memories of My Town. Rizal is often regarded as the "father" of the Philippines or a national hero. He wrote this poem:

When I recall the days

That saw my childhood of yore

Beside the verdant shore

Of a murmuring lagoon;

When I remember the sighs

Of the breeze that on my brow

Sweet and caressing did blow

With coolness full of delight; When I look at the lily white

Fills up with air violent

And the stormy element

On the sand doth meekly sleep;

When sweet 'toxicating scent

From the flowers I inhale

Which at the dawn they exhale

When at us it begins to peep; I sadly recall your face,

Oh precious infancy,

That a mother lovingly

Did succeed to embellish.

I remember a simple town;

My cradle, joy and boon,

Beside the cool lagoon

The seat of all my wish. Oh, yes! With uncertain pace

I trod your forest lands,

And on your river banks

A pleasant fun I found;

At your rustic temple I prayed

With a little boy's simple faith

And your aura's flawless breath

Filled my heart with joy profound. Saw I God in the grandeur

Of your woods which for centuries stand;

Never did I understand

In your bosom what sorrows were;

While I gazed on your azure sky

Neither love nor tenderness

Failed me, 'cause my happiness

In the heart of nature rests there. Tender childhood, beautiful town,

Rich fountain of happiness,

Of harmonious melodies,

That drive away my sorrow!

Return thee to my heart,

Bring back my gentle hours

As do the birds when the flow'rs

Would again begin to blow! But, alas, adieu! E'er watch

For your peace, joy and repose,

Genius of good who kindly dispose

Of his blessings with amour;

It's for thee my fervent pray'rs,

It's for thee my constant desire

Knowledge ever to acquire

And may God keep your candour!

Jose Rizal is considered a national hero who inspired the Filipino resistance during Spanish colonization. Philippine history spans periods of colonization by Spain, the United States, and Japan: three centuries under Spain, over forty years under the U.S., and a brief period during World War II under Japan. The Philippines only became an independent republic in the 1940s. This poem reflects Rizal’s nostalgic recollection of his hometown and its landscapes, linking nature closely with the idea of home.

While I understand why this poem might have moved people at the time, I find it harder to resonate with it from my contemporary perspective. Having not experienced the historical context firsthand, it’s difficult for me to grasp what made this poem so impactful. However, analyzing it within its historical context, I see how Rizal’s reflections on his homeland’s landscape would evoke strong emotions, particularly during his exile. He lived to only 35 years old, spending much of his youth in exile in Europe, later moving to Hong Kong, and eventually being banished to Mindanao by the local colonial government in the Philippines. During this time, his memories of home and its landscapes likely became a powerful source of emotional connection for him and others.

What strikes me most is how, despite over 300 years of Spanish colonization, the Philippines managed to reconstruct its national and cultural identity as a unified nation. The Philippines consists of over 7,000 islands and 80 languages, and I’ve asked my Filipino friends about this. They’ve told me that these geographical and linguistic divides made it nearly impossible to build a cohesive nation, culture, or identity during those 300 years.

Rizal is regarded as a national hero, yet it is fascinating to note that he didn’t lead the final rebellion. Instead, he inspired the rebellion’s leaders, which led to his arrest and eventual execution by the colonial government. This process feels almost theatrical—like a dramatic narrative my Filipino friend described as “cartoonish”: one hero falls, another rises, and a new government or nation emerges. The voices of ordinary people, however, seem absent, with the populace instead being led by heroic figures.

When viewing this exhibition, my first instinct was to avoid reading the accompanying text, knowing that discussing plants in this context often carries preconceived notions. Still, I found certain clues in the artworks themselves. While I see this as a response, it is not a direct critique of colonialism. Much of the work—like the videos we saw earlier—is presented through paper cutting or installations.

The artist is deeply interested in history, but the archival images used in the exhibition come from the American occupation of the Philippines, which is a different era from the poem by Jose Rizal that he references. This displacement of time feels like something that happens frequently in art exhibitions. Yet, when I consider the resources as a whole, it starts to make sense. The artist uses installations to shroud these images in shadows, evoking the lingering ghost of colonial history and its enduring influence.

In the text, the artist mentions that history is not a conclusion but a medium for reshaping postcolonial imagery of the past and present. This is, of course, his perspective—and the curator’s interpretation, not the artist’s own words. I have some doubts about this, but I think it’s worth setting aside for now. We can revisit it later.

Installation view of Feast and Famine, kurimanzutto, Mexico City, September 22–October 24, 2015

Installation view of Feast and Famine, kurimanzutto, Mexico City, September 22–October 24, 2015

Hangping: Another exhibition I want to mention was created by a Mexican female artist, Minerva Cuevas, and focused on chocolate and cacao. The exhibition, titled Feast and Famine, featured numerous chocolate sculptures and incorporated archaeological motifs and archives. Held in Mexico, the artist responded to local myths as well as colonial-related themes.

Minerva Cuevas, Bitter Sweet - Hershey’s (detail), 2015

Minerva Cuevas, Bitter Sweet - Hershey’s (detail), 2015

For example, in one of Minerva’s works, she used chocolate to recreate an image depicting a European cannibalism story. I found it to be quite satirical and humorous. The fact that chocolate is edible adds another layer of meaning, making her use of symbols and the cultural context of the material itself particularly brilliant.

During a studio visit, I had the chance to interview her. I asked how an artist so adept at working with symbols goes about selecting them. She shared a video with me during the visit, and after watching it, I had even more questions.

For instance, in the video, an elderly woman mentioned that when squirrels come to eat cacao beans, she doesn’t feel bothered because it’s simply part of their life. This sparked a rather extreme thought in my mind. From a biological perspective, when colonizers arrived in this region, it was essentially a process of seizing an ecological niche. If we consider humans as two different species, then the colonizers might be seen as a different "species" to the indigenous people of the colony. In this sense, how different is their arrival from the squirrels taking her cacao?

It was a provocative and radical question that crossed my mind at the time, but I didn’t voice it out of concern that the artist might find it offensive.

For instance, it can seem like it’s merely presenting a conflict between Mexico and Spain, or more broadly, a struggle within the postcolonial context between a former colony and its colonizer. Yet, upon closer examination, the argument that cacao originates in Mexico—and thus the cultural critique—isn’t entirely solid. Cacao is more accurately native to Central America as a whole.

This creates a sense of dislocation, conflating Central America with Mexico and framing it as the "Orient" relative to the "Occident" of the West. I’ve always had some doubts about this perspective, so I hope we can discuss it later.

Similarly, in the earlier exhibitions by the Filipino artists, we saw narratives about how the Philippines, through its anti-colonial struggles, gradually formed a nation. But even now, has it truly solidified? The stories often feel like cartoonish hero narratives.

In both exhibitions, plants are transformed into images or symbols. That’s the point I wanted to highlight in this part of my discussion.

In Mexico, there are many traditional gardening or farming methods, such as the "Three Sisters" technique. This involves planting tomatoes, corn, and squash together. The corn provides a stalk for the tomatoes and squash to climb, while the tomatoes repel pests with their scent, protecting the other plants. This practical approach had little to do with the geometric or formal aesthetic trends seen in European gardens.

I also found Hang Ping's mention of squirrels very thought-provoking. When the United States colonists first arrived on the American continent, they viewed Native Americans not as humans but as complete "others." Early American settlers or frontiersmen referred to the land as a "fertile virgin land"—a place of boundless forests and rich soil. These forests were said to be inhabited by "wild animals," but what they meant by animals often included the indigenous people, equating them with nature itself.

Many of the native gardens, which settlers redefined as untouched wilderness, were in fact deliberately planted to harvest fruits and other resources. From a non-native perspective, these human-made gardens were reframed as pristine nature.

It’s also fascinating how today’s discussion seems to keep circling back to Spain—whether it’s pineapples, the Philippines, or now Mexico. I currently work in a garden research institution in Pasadena, California. This area was once a large ranch owned by the Spanish crown and managed by a governor. Today, however, there are no traces of the Mexican or Native American communities who once lived here.

In Pasadena, many Mexican workers serve as landscapers or gardeners for the city’s large estates, as the homeowners often lack the time to maintain their gardens. Yet these gardens are symbols of their wealth or social status and require upkeep. Most of the landscapers in Pasadena are Mexican.

In the 1960s, a local nursery and bird market in Pasadena caught fire, releasing a flock of red-headed parrots native to Mexico. These parrots didn’t return to Mexico because the Californian climate was perfect for them. Today, the parrots are so widespread that you can hear them screeching noisily every morning and evening.

On my way to work, I often see Mexican gardeners wearing wide-brimmed straw hats, a distinct symbol of Mexican culture, tending to gardens in predominantly white neighborhoods. Because California is so dry—essentially a desert climate—these gardens often feature agave and succulents, which are native to Mexico. In front yards, there’s often a large California orange tree under which a Mexican gardener tends to the plants. Above him, you might see a flock of Mexican parrots noisily eating oranges.

This surreal, disorienting scene is a fascinating mosaic of cultural fragments. It combines symbols we associate with various cultures into a new, layered image. The scene is both contradictory and captivating.

When chatting with these Mexican gardeners, they often mention having small vegetable plots back in their hometowns. They bring seeds to California to grow familiar plants, maintaining a connection to their homeland. They also talk about how landscaping work in the U.S. differs from Mexico. The U.S. system is highly mechanized, with regulations dictating what can and cannot be done, and traditional Mexican methods are often replaced to increase efficiency.

My research involves overseas Chinese gardens, and I often find myself tending gardens with Mexican workers who frequently express confusion about Chinese gardening practices. These interactions reveal the fascinating process of adaptation and collision, where both techniques and plants take root in a new environment. This process itself is incredibly interesting and closely resembles Rubén’s photography.

While his images focus on Mexican topiary, the practice itself originates in Europe and evolved further in Mexico. From a single image, it’s difficult to immediately grasp the intricate transformations behind it. Similarly, as Jiang Yao mentioned about pineapple rentals, it’s hard to extract such detailed stories from a single photo. Yet the photographic medium can focus our attention on specific elements, opening a window to a new world.

For me, this shift in perspective—whether during research or just daydreaming—is one of the most delightful parts of the process.

I’m also intrigued by Jiang Yao’s mention of pineapple rentals. In the 16th and 17th centuries, what was life like for Chinese migrants? For example, in the last century, many Chinese immigrants in South America gravitated toward specific industries, such as opening grocery stores. Was pineapple rental a widespread group phenomenon or a niche practice?

The example of pineapple rentals, as well as another case from the 19th century—where someone was convicted for stealing five pineapples from a plantation and subsequently sentenced to five years in Australia—highlights a patchwork of fragments. At the time, Australia was a remote penal colony for Britain. These scattered pieces of information reflect what Zheming mentioned as a way of piecing together narratives.

When we consider the symbolic significance of pineapples from a non-Western, non-colonial historical context, they’re just an ordinary fruit to us. When you get a pineapple, the first thing you might think of is soaking it in salted water to avoid its sting. This reaction is far more mundane and lacks the strong symbolic connotations often attached to pineapples in Western colonial histories.

Speaking of symbols and objects, I’d like to share some paintings.

Historica Graphica Collection/Getty Images

Jiang Yao: This is a painting from the Dutch Golden Age, around the 17th century, featuring a pineapple. For about 20–30 years in the early 17th century, Brazil was a Dutch colony. After the Dutch withdrew and Brazil ceased to be their colony, these paintings seemed to function as symbolic representations for Dutch artists—or the Dutch people—to imagine Brazil, a land they once colonized. Pineapples, one of Brazil's places of origin, often appear as prominent motifs in these paintings. For example, in Frank Post’s works, pineapples frequently occupy the foreground on the left, serving as a strong symbol in the Western context.

Connecting this Western context to the Chinese communities mentioned earlier and Hang Ping’s discussion of colonial reflections in the Philippines, I recently had conversations with friends in Singapore, revealing another perspective. In Singapore’s historical narratives, they often compare British and Japanese colonialism, viewing British rule as "good" and Japanese occupation as "bad." From 1942 to 1945, during World War II, Singapore experienced a brief three-year Japanese occupation, which is described in their histories as a period of extreme suffering and decline. Yet, when discussing the much longer period of British colonization, the narrative shifts to one of Britain laying the foundations for Singapore’s development, offering an entirely different tone.

Regarding Hang Ping’s earlier point about dislocations or misreadings, Western narratives often frame places like Central America, relative to Europe, as a kind of "Orient." Pineapples are an example of this. When Columbus brought pineapples from Guadeloupe to Spain in 1495, he mistakenly thought he had reached India, calling the fruit an "Indian" discovery. Modern texts clarify this by referring to the region as the "West Indies," but this misattribution highlights the numerous dislocations within Europe-centric historical writings, similar to the fragmented imagery Zheming observed in Pasadena.

In the Southeast Asian or Asian context, however, pineapples are more ordinary and less symbolic. In Singapore, where I am currently conducting research on pineapples, people often ask why I didn’t choose to study durians instead. To them, pineapples are seen as commonplace. While Western Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries referred to pineapples as the "fruit of kings," Singaporeans regard durians as the "king of fruits" and mangosteens as the "queen of fruits," with no significant connection to pineapples.

When asked what comes to mind when they think of pineapples, many Singaporean Chinese mention pineapple tarts, often eaten during Chinese New Year, or pineapple juice. For them, pineapple juice is a simple, everyday beverage. Interestingly, in Singapore, people refer to pineapples as huang li in Mandarin, while in Taiwan they’re called feng li, and in Hong Kong, they’re called bo lo. These regional naming differences reflect the localized familiarity with the fruit.

Let me briefly introduce the demographic composition of Singapore. Singapore’s identity card includes a classification system called CMIO: C stands for Chinese, M for Malays, I for Indians, and O for Others. The majority of Singapore’s population—over 50%—is Chinese. Historical accounts suggest that this composition is closely tied to the plantation system of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

While Europeans described the Americas as "fertile lands," they referred to Singapore as a treacherous region full of forests, swamps, and waterways. To establish settlements or plantations there, significant manpower was required. In the 19th century, the British introduced a system called the "Kongchu" or "Headman" system, where a landowner (or Kongchu) was granted authority over a plot of land and encouraged to bring relatives or acquaintances to clear and cultivate it. As a Kongchu, you enjoyed privileges, including the right to sell opium. The name "Kongchu" reflects the environment of the time, as these plots of land were often encircled by rivers and forests, requiring extensive clearing and cultivation.

Much of Singapore’s land was initially developed under this plantation system. While plantation systems in colonial contexts are often discussed critically, especially for their exploitative nature, the discussions I’ve encountered in Singapore sometimes offer a different perspective.

Returning to the point about Singapore’s foundations being built on plantation systems: almost every inch of land here is linked to this history. This system required a diverse workforce, which contributed to the multi-ethnic composition we see today in Singapore.

Diagram of pineapple canning factories recorded on a 1945 Singapore survey map, compiled and presented by Jiang Yao based on primary and secondary sources.

Diagram of pineapple canning factories recorded on a 1945 Singapore survey map, compiled and presented by Jiang Yao based on primary and secondary sources.

Jiang Yao: Talking about the connection between population composition and agriculture, I’d like to return to the term huang li (pineapple). This term originates from Hokkien, a southern Min dialect. While Hokkien is often translated as "Fujianese," a search on Wikipedia shows it specifically refers to the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou regions of Fujian province. Among the Chinese communities in Singapore, there are five major dialect groups: Hokkien, Hakka, Hainanese, Cantonese, and Teochew.

Huang li seems to be more familiar to many people because the pineapple trade and cultivation were predominantly undertaken by Hokkien people. One notable Hokkien individual is Tan Kah Kee, who built many schools and hospitals in China. He initially made his fortune in Singapore by growing pineapples and later moved into rubber cultivation. Historical records show that the pineapple industry—from plantations to factories and street vendors—was largely dominated by the Hokkien community. The Cantonese, on the other hand, were more focused on the rubber trade, while Teochew vendors often sold pineapples carrying baskets, and Cantonese vendors tended to use pushcarts.

While pineapple rental doesn’t seem to have been a group phenomenon, the history of huang li in Singapore reveals how it became a primary means of livelihood and economic sustenance for the Chinese in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pineapples also served as a cultural and economic bond, connecting people of the same dialect group.

This brings us to the plantation system and another crop that coexisted with pineapples in early 20th-century Singapore: rubber. Rubber was a highly lucrative cash crop in the early 1900s, especially during the rubber boom of 1910, when Singapore rapidly established large rubber plantations. Rubber became a key colonial crop for the British, cultivated in extensive plantations.

Criticisms of rubber plantations often focus on their exploitation of land and labor. In contrast, pineapple plantations seemed to escape similar critique. The British engaged in the pineapple trade but refrained from large-scale pineapple cultivation, as it was less profitable than rubber. Pineapple plantations were thus taken up by the Chinese, who lacked the vast capital required for rubber plantations.

From my perspective, the operational model of pineapple plantations in early 20th-century Singapore differed significantly from the imperial plantations typically associated with colonial exploitation. This is not to downplay the importance of reflecting on the exploitation of land and labor in plantation history, but rather to suggest that the history of plantations invites alternative discussions. For example, pineapple plantations in Singapore were closely tied to the formation of identity bonds among Chinese dialect groups.

When immigrants arrive in a foreign land, forming social and economic connections is essential for integrating into society. The history of pineapple plantations in Singapore provides a supplementary perspective—less connected to Spain but nonetheless a unique structure relevant to discussions about plants, colonialism, and memory.

Speaking of memory, another interesting piece of historical material involves the Bugis people. Around the 1850s, the Bugis—a group from Indonesia—came to Singapore and engaged in pineapple cultivation. Known as Bugis Chinese or Ethnic Chinese, they would collect pineapple seedlings. A pineapple plant has several parts suitable for propagation. The crown (the top of the pineapple) is often used today for water propagation, where it is placed in water until roots grow before being planted. Beneath the crown are slips and suckers, found on the sides and base of the pineapple stem. Even the roots themselves have buds.

When the Bugis and Chinese cultivated pineapples, they selected different parts of the plant for propagation, which led to variations in covering methods, planting density, and fertilization techniques. This highlights that human interactions with plants are not static; these subtle differences are closely tied to the diversity of human communities and their practices.

The other day, I was telling Jiang Yao about a podcast I listened to by Lu Yu. The theme was interviewing as a form of deception, which I found quite accurate. Images and archives often possess a journalistic quality—they’ve been edited or manipulated. For example, when someone commissions a portrait, they’ll often request to be painted more attractively. This isn’t an absolute reflection of reality.

Whether in our perception or in retrospection, we’re always attempting to approximate the truth, but we’ll never fully grasp what happened in the moment. For me, the task of history and art isn’t to trace origins—that’s more the domain of linguists, archaeologists, or biologists, who directly pinpoint facts about where something came from. Our work focuses on how history has been altered and how we can push these narratives toward greater richness and complexity, avoiding overly simplistic interpretations.

Recently, I’ve been reflecting on my own work and feel that beginning with the biological aspects of a subject can lead to a more open perspective. For example, while working on The Wandering History of Pineapples, I came across an intriguing yet unverified theory. It suggested that the mass slaughter of indigenous peoples in the Americas by colonizers triggered a “Little Ice Age” through a butterfly effect, leading to agricultural collapse and, eventually, the fall of the Ming Dynasty.

I’m not interested in proving or disproving such causal relationships, but rather in the balance between the environment and biological systems. Someone earlier mentioned squirrels. Recently, we visited Yunnan and observed farmers growing corn. I vividly remember one farmer discussing how field rats or squirrels could wreak havoc on cornfields, sometimes leading to massive crop failures.

Someone might argue that squirrels are small and can’t eat much, but if you replace them with field rats or locusts, the impact on humans could be catastrophic. Humanity’s response to these threats often involves adapting technologies, such as improving farming techniques or developing tools tailored to specific environmental conditions.

For instance, a gardening tool originally made of wood might need to be replaced with iron because wood doesn’t last as long. This shift toward a biological perspective expands the scope of discussion. It’s not just about the conflict between Mexicans and Spaniards. What defines a Mexican or a Spaniard? Should new Spanish immigrants bear responsibility for colonial-era injustices?

If we examine the biological impact of squirrels, rats, or locusts on humans as a species, can we similarly explore how indigenous peoples were perceived as a threat by Spaniards? This moves the discussion beyond cultural constructions.

The common narrative emphasizes massacres and uses imagery to reflect on these events, which often leads to specialized, academic discussions. However, when you broaden the lens to consider environmental connections, historical understanding also expands.

This is the framework through which I approach my own artistic practice, which is deeply intertwined with Plant South Salesroom's work. Much of it has emerged through collaborations with Jiang Yao and other members, sparking insights along the way.

Domestica, 2024, Yang Hangping

60 × 25 × 120 cm

Materials: Plastic molds, paper, "wild grass," plastic thatch, metal spikes, cardboard box, metal chain.

This piece is titled Belong to the Land and is composed of a model train set belonging to Thomas and His Friends, bricks from a nearby construction site, a flag, and a pipe reel from farmland. The pipe reel is used to facilitate the movement of long irrigation pipes in farmland by allowing them to be placed through the reel's loop for easier handling.

It is a visual collage that incorporates archival elements, such as symbols from tunnel engineering. Since the exhibition was originally planned to take place in Jiangxi, we referenced the route from Zhejiang to Jiangxi and designed the piece with a sense of linearity and imagery. Although the exhibition ultimately didn’t come to fruition, the piece was completed with this route-inspired design in mind.

Becoming Furniture: Furnished (Partial), 2024

Site-specific installation, variable dimensions

Materials: slope protection plastic molds, LED light strips, plastic dust proof fabric, rush grass, palm mats

This piece is a bed made from palm mats, rush grass, and dustproof fabric. When creating these works, I wasn’t focused on expressing specific meanings through individual pieces. Instead, I aimed to combine them, allowing each to provide different clues and perspectives, encouraging reflection or sparking ideas in the viewers.

The next piece relates to the construction of tunnels for high-speed rail or highways. When tunneling through mountains, U-shaped or ecological slope reinforcements are often placed nearby, surrounded by concrete, resembling a small garden where grass is planted.

The lower section of the piece features a casting mold for slope reinforcement, while the upper section includes rush grass that I brought back from Jiangxi and Fuzhou. At the base, there is an LED light strip, and an audio recording is played on-site.

Becoming Furniture: Furnished (Partial), 2024

Site-specific installation, variable dimensions

Materials: slope protection plastic molds, LED light strips, plastic dustproof fabric, rush grass, palm mats

Hang Ping: This audio was recorded on a bus (click to listen), and we’ve provided a brief introduction in our official WeChat article. Since it’s a found object, I’m particularly interested in uncovering the information behind it and organizing that into a meaningful structure. The focus of this exhibition is tunnels—a subject that often goes unnoticed when discussing the relationships between infrastructure, the environment, and people.

Previously, we’ve conducted fieldwork following different projects, some focused on agriculture, others on rural studies. In these places, anthropologists and ethnographers often use oral histories as a way to engage and investigate, and the information they gather has some overlap with archives or questions of perception that we’ve discussed before.

In creating this work, I realized that simply understanding how someone perceives their environment or situation through their own words doesn’t provide a complete picture of the village. For instance, a villager might mention that they used to work at a forestry station before leaving to find work elsewhere. Driving, for example, might have been a relatively rare skill at the time, allowing them to become a coal truck driver or freight hauler. Over time, as more people took up freight driving, they might have lost their job and shifted to passenger transport, eventually working as a driver in the nearby town.

For the village, this is a story of one person migrating to the county town—not a great distance—but how they made this journey is often overlooked. How much did the environment shape their journey?

Ethnographers studying "untouched" or unmodernized areas often focus on local cultures—rituals, religions, and traditions of people who seem to live well in their villages. But I’m curious about how they communicate with the outside world. Why do they choose to stay in these places when trade is constantly happening? How much of a role does technology play in these choices?

This reflection parallels what Zheming and Jiang Yao previously discussed, whether it’s about crop domestication or horticultural pruning: what role does technology play, and how do we evaluate its impact across different variables? These are questions current research is attempting to address, and I aim to explore them through the medium of exhibitions. This is a defining characteristic of the project.

The Weather at the Time Exhibition View, 2023; Yang Hangping; Photography: Wang Jiajun; Schein Space

The Weather at the Time Exhibition View, 2023; Yang Hangping; Photography: Wang Jiajun; Schein SpaceHang Ping: Previously, we also worked on an exhibition more closely related to plants, focusing on citrus fruits. For that exhibition, we produced a zine titled The History of Citrus. Unlike pineapples, this exhibition covered a wide variety of fruits, such as pomelos, mandarins, citrons, and Buddha’s hand, forming a family of sorts.

During the process, I became curious about how humans have influenced these fruits and, in turn, how the fruits have impacted humans. For example, in the collages on this piece of fabric, I combined various citrus fruits to create something akin to a family tree. However, this "family tree" is highly inaccurate—it’s less about factual representation and more like what happens when someone alters a family’s history to tell a story.

Another piece in the exhibition uses insect secretions as the coating, often applied to fruits for preservation. Since the works are presented in what feels like a citrus storage space, I chose to use interior design elements such as curtains, lamps, and flooring to enhance the presentation.

This approach reflects my focus on topics beyond postcolonialism. When discussing citrus fruits, for instance, they are found all over the world. It’s difficult to trace their precise routes, and when something predates human history by a significant margin, it becomes challenging to interpret it solely through the lens of colonial or postcolonial discourse.

Instead, I’m more interested in the results of domestication and commodification, as well as the relationships between citrus fruits and other materials. This perspective feels cooler, less emotionally charged.

When I encountered the works of the Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas, I found myself questioning whether my feelings stemmed from the artwork itself or from an educationally instilled sense of nationalism and anti-colonial sentiment. In contrast, when I worked with the citrus materials—peeling oranges or handling the components—I felt a much calmer, more detached sense of engagement.

This detachment, in a way, pulls away from the "rescuer mentality" often exhibited by intellectuals. Many people, when visiting a place—even when working with plants as a subject—immediately jump to seeing pineapples or chocolate as cultural symbols. They might think, "As a Mexican, as a Chinese, how should I respond?" This sudden awakening of a savior’s spirit drives them to critique and resist these cultural narratives.

However, when placed in a broader context, the discussion doesn’t have to revolve around postcolonialism. These plants aren’t solely tied to colonial history—they’re also connected to weather, squirrels, and other factors. This broader perspective diminishes the likelihood of strong nationalist emotions.

Regarding the use of local materials, it’s increasingly rare to find something purely "local." During the production process, the machinery might be foreign, the technology imported, but the resources local. Does that make the product local or foreign? If these elements are so intertwined, should we even make such distinctions?

In artistic practice, it’s less about resolving doubts and more about raising countless questions. This reflective process becomes part of the research itself, questioning whether our original understanding or narrative is truly accurate.

Lin Haodong: Today's panel discussion has followed two very clear threads.

One is the contrast between the plantation system in Singapore, as mentioned by Jiang Yao, and the traditional colonial plantations emphasized by Zheming. The other is the contrast Hang Ping highlighted between official archives, firsthand documentation, and artistic creation.

In some ways, I think artistic creation can come closer to the so-called historical truth than official narrative archives.

That said, I’m still very curious about the points Zheming mentioned earlier regarding Mexican critiques of Chinese gardens. What exactly did they find unreasonable?

For example, Mexican gardeners often clean the moss off steps or stones, as they see it as dirty and unnatural. To them, a natural stone should simply be a stone. In contrast, Chinese gardeners value the moss, seeing it as beautiful and natural. They might even intentionally grow moss during spring by watering the stones with rice water. To the Chinese, moss thriving on a stone represents the most natural state of that stone in its environment. This highlights a fundamental difference in the understanding of "nature"—whether it’s seen as something "natural and spontaneous" or governed by the Daoist philosophy of ziran (naturalness).

Another example involves trees. A particular branch shape might seem unsightly to a Mexican gardener, prompting them to prune it, while a Chinese gardener might find the shape interesting and insist on preserving it. This difference arises from contrasting cultural perceptions and aesthetic preferences.

There are many such differences. A particularly intriguing example is that the Chinese garden I work at employs an American bonsai enthusiast with a Lingnan (southern Chinese) bonsai background. He cultivates bonsai using local Californian plant species. However, his understanding of these plants’ biological characteristics, growth habits, and rates isn’t as thorough as that of the Mexican gardeners. When making bonsai with Californian plants, he relies on the Mexican gardeners’ practical experience and knowledge about the plants. These are then transformed into traditional Chinese bonsai styles, even incorporating the Lingnan aesthetic. Essentially, it’s about integrating one knowledge system into another.

Another noticeable difference is that Mexican gardeners often use leaf blowers to clean up fallen leaves completely, but from a different perspective, leaving fallen leaves under trees can have certain ecological benefits. Different management practices and understandings can lead to conflicts. For instance, nursery protocols in the U.S. often require fallen leaves to be cleaned thoroughly to prevent fire hazards, something that many gardeners from Asia find hard to grasp.

In the Japanese dry garden (karesansui) at the institution where I work, everything is meticulously cleaned. However, the gardeners maintaining the adjacent moss garden might sweep up the leaves only to casually toss a few back on the moss, creating an intentionally imperfect aesthetic. It feels a bit contrived, but it reflects how cultural preferences vary under different cultural contexts.

Hang Ping: So, how’s the moss in your garden now?

Taro Zheming: It’s all been removed. After it was cleared, people started asking, "Why did you scrape it all away?"

Jiang Yao: That sounds like something a museum would do—like maintaining an exhibition space.

Taro Zheming: Exactly. For instance, in Chinese gardens, when Taihu rocks are arranged in a well or other feature, the rocks are meant to look as though they naturally rise from the ground. If you clean off all the moss and fallen leaves around the base and expose the concrete foundation beneath, it completely ruins the aesthetic.

In contrast, a Mexican garden might prioritize tidying up the space, focusing on keeping everything visibly clean.

Street Trees & Pollarding

Pollard Birches, Vincent van Gogh, 1883,(Collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Netherlands)

Lin Haodong: I recall that our outline includes a discussion about street trees.

Taro Zheming: Yes, street trees are closely tied to pruning. One feature I find particularly fascinating is Nanjing's famous plane trees. They have a large trunk with two to four long lateral branches that grow out, forming an unusual shape. While inspired by the appearance of street trees in London and Paris, their pruned shapes in Nanjing have a distinct Chinese aesthetic, often referred to as the "champagne glass" style.

When Nanjing constructed its new wide roads, there were many areas exposed to intense sunlight. To provide shade, trees with horizontally spreading branches were needed. If you look at old photos of Nanjing, the plane trees initially planted along the streets were tiny—just saplings with trunks about the thickness of a fist, bare of branches. By cutting off the terminal buds, gardeners encouraged lateral buds to grow and shaped the trees accordingly.

This ties into my earlier research on pollarding. Let me share a few images. The term "pollard" in English comes from "poll," which means to cut off the top. These images are likely familiar to many, often seen in Spain, France, Italy, and the UK. Pollarded trees look "beheaded," with several thick, stubby branches that sprout finer twigs, forming a dense canopy.

This method produces a lush crown, and in summer, people often sit under these trees for shade. However, during the 18th century, this aggressive pruning style faced significant criticism across Europe. One reason was its unnatural appearance, as unnaturalness was deemed unappealing at the time. This was especially true in Britain, where tensions with France led to a rejection of French-style formal gardens. The rigid and symmetrical aesthetics associated with France were widely criticized, while Britain began championing the naturalistic style of Chinese gardens.

Despite the criticism, pollarded trees could still be found on British streets. Interestingly, while the style might appear distinctly European, similar pruning techniques have a long history in China. For example, in remote areas of Tibet, Sichuan, and Yunnan, you can still find willow, jujube, elm, and mulberry trees pruned in this manner in village landscapes.

The shaping of Nanjing's street trees also wasn’t primarily for aesthetic reasons but to provide shade. While their forms may resemble European styles, their purpose aligns with practical concerns, much like historical pruning practices in China.

Pollarded Willows in Chinese Classical Painting, Detail from The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll VII, (Collection of the University of Alberta Art Museum, Canada)

A key feature of pollarding is that it encourages the ends of the branches to sprout numerous dense shoots. For mulberry trees, this pruning is done to harvest leaves for silkworms, while willow trees are pruned to collect branches for making furniture, fences, or agricultural tools. If the interval between prunings is longer—say, five years—the branches grow thick enough to be used as hammer handles.

This method is highly practical. It’s only later that people assigned an additional layer of aesthetic value to it, transforming it into an artistic symbol. However, the aesthetic trends associated with this symbol often shift depending on the political, economic, and technological contexts of the society.

Pollarded Willow Trees Along the Riverbanks Near Hangzhou in the Early 20th Century, From the Charles Lang Freer Collection of Chinese Photography

(Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA)

Taro Zheming: To conclude, let me show you a photo of pollarded trees along the riverbanks in Hangzhou from the early 20th century. When I first encountered pollarding in ancient Chinese paintings, I wasn’t sure if it was a stylistic choice by the artist or something that existed in reality. It was only after consulting historical Chinese agricultural and administrative texts, as well as old photographs like this one, that I confirmed it was indeed a traditional pruning method used in China for centuries.

Over time, later generations added aesthetic interpretations to this pruning style, transforming it into a symbol of beauty in art. However, it was originally a very practical technique.

I became interested in the shapes created by pruning, especially in fruit trees. For example, in France and Italy, fruit trees are often pruned into flat shapes to increase fruiting efficiency. While this practice is highly functional, it also inadvertently turns something practical into something visually appealing—an example of the ingenuity of farmers.

What I eventually realized is that much of this traditional knowledge is now viewed through a purely visual lens by contemporary designers. It’s judged based on whether it looks good or fits a particular style, but this often overlooks its practical origins and its ties to agriculture and forestry. These practical attributes were the real reasons for the shapes, rather than purely aesthetic considerations.

Jiang Yao: When Hang Ping shared his projects, he mentioned focusing more on the biological significance of things. Similarly, Zheming just spoke about observing the intrinsic states of horticultural plants themselves. This approach seems to make it easier for us to break away from subconsciously entering constructed symbolic contexts.

Jiang Yao: When Hang Ping shared his projects, he mentioned focusing more on the biological significance of things. Similarly, Zheming just spoke about observing the intrinsic states of horticultural plants themselves. This approach seems to make it easier for us to break away from subconsciously entering constructed symbolic contexts.When you mentioned pollarding, it reminded me of when we worked on citrus. We came across various pruning shapes, including one called the "heart shape." It’s named for its resemblance to a heart and is somewhat tower-like. This shape ensures sunlight reaches all parts of the plant, including the innermost areas, not just the outer layer, which improves both the fruiting rate and ripening uniformity of the entire tree.

Taro Zheming: When I was researching fruit trees and designing orchards, I often wondered why the spacing between fruit trees was so wide if the goal was to maximize yield. Why not plant them closer together? Initially, I thought it was to prevent competition between trees for water and nutrients. But later, I discovered that the spacing was determined by the tools used for orchard management.

For example, the size of small trucks or carts used by workers dictates the spacing between trees. It’s a highly practical consideration. In fact, tree spacing has been increasing because modern automated harvesting trucks are larger, necessitating wider gaps between trees.

As designers, we might try to come up with a complex, theoretical explanation, but once you’ve been involved in the actual process, you realize it’s a perfectly logical and straightforward decision. Only by engaging in the physical task can you understand its rationale. Without that embodied experience, any description or interpretation risks being an outsider’s perspective.

Jiang Yao: I remember when people talk about history, they often emphasize that it’s not a complete picture of the past—it’s what has been recorded by certain people. We often say that to understand history, you have to place it in its spatial and temporal context and imagine what things were like at that time.

The orchard example reminds me of a pineapple farmer I know in Xishuangbanna who practices ecological farming. He said the planting density for pineapples is usually quite high in industrial farming, with yields of 3,000 to 4,000 kilograms per mu (about 0.067 hectares). This is based on a double-row planting technique introduced in the 1980s. However, he can’t adopt this large-scale industrial method because he removes weeds manually. His planting spacing has to be wide enough for him to navigate the rows wearing a backpack-style weed trimmer.

This highlights the importance of embodied experience in practical tasks—it’s a way to engage with the present reality. In contrast, when it comes to history, we can’t always revisit or physically experience the past. Instead, history becomes a process of revisiting a site or entering a particular time and space.

Another thing I find fascinating is the skepticism many people maintain toward existing narratives or written histories. They don’t necessarily see them as complete or definitive. In the podcast about interviewing that I mentioned earlier, there was a point about how interviewees often deliver responses that have been rehearsed—they’re accustomed to presenting their stories in a certain way, and what they say may not even be entirely true.

So, what is "truth"? Perhaps there is no absolute truth. All we can do is continuously approach it by piecing together fragments and perspectives to construct a more accurate picture.

Taro Zheming: I think studying history is incredibly challenging. It demands a profound level of knowledge and involves a relentless process of questioning and self-reflection, which can be quite painful. That’s why I chose to focus on historiography instead—the study of how history itself is written.

This approach examines the context and background in which historical narratives were crafted, deconstructing the perspectives and cultural systems of the time. For me, this is somewhat easier and far more engaging—analyzing the frameworks and cultural milieus that shaped how history was written back then.

Taro Zheming: Actually, there isn’t much of a direct connection. When we talk about overseas replicas of Chinese gardens, it’s important to distinguish between two periods: the chinoiserie gardens of the 18th century and the classical Chinese gardens built overseas in more recent decades.

The chinoiserie gardens in 18th-century Britain were somewhat influenced by colonialism, but in most cases, the people designing them had never been to China. Their imagination of China was based on descriptions from a few missionaries or imagery on porcelain. These gardens were purely fantasies of the Orient, constructed through Western interpretations of Chinese aesthetics.

The overseas classical Chinese gardens we see today emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, and these have no colonial connection. Their purpose was rooted in diplomacy. For instance, after the normalization of U.S.-China relations, two major cultural exchanges were initiated: China gifted giant pandas to the United States, and a replica of a Suzhou-style classical garden was built in New York. Chinese gardens became a cultural export.

The garden where I currently work in California was designed by a Suzhou garden company specifically for the local Chinese-American community. While the garden itself is deeply influenced by Californian aesthetics and usage, it serves as a space for local Chinese people, making it a product of transnational and cross-cultural fusion. In this context, the Chinese gardens built overseas after the 1980s have little to do with colonialism.

Hang Ping: Since you mentioned cultural diplomacy, I recall a discussion we had with Jiang Yao and a German garden caretaker during an online Sino-German forum. They mentioned that funding for maintaining classical gardens has been decreasing, making this kind of diplomacy feel less viable over time.

I also read an article about Black Myth: Wukong, a video game that transforms traditional Chinese architecture into an interactive experience. The game has sparked interest among players to visit real-world locations featured in the game. I wonder if this could be a new form of cultural diplomacy. What are your thoughts, Zheming?

Taro Zheming: The first overseas Chinese garden was built at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Because it was created in a museum context, it was expected to have "authenticity," so the garden was essentially a copy-paste project. A courtyard was directly transplanted from Suzhou to the museum, emphasizing the cultural attributes of Suzhou gardens as a pinnacle of Chinese literati thought. However, the non-human elements of the garden, such as its living plants, were neglected. The walls remained perpetually pristine, and many of the plants couldn’t survive indoors, resulting in the use of plastic plants.

This focus on "authenticity" renders the garden lifeless in the eyes of many garden scholars. German gardens face similar issues—they lack user groups or communities that truly love and maintain them.

In contrast, the garden I’m involved with in California, Liu Fang Yuan (the Garden of Flowing Fragrance), is entirely different. It was designed for the local Chinese-American community, which has invested heavily in its growth and maintenance. The garden began construction in the early 2000s, with its third phase recently completed, making it the largest Chinese garden outside China. Plans for a fourth phase are already underway. This success is rooted in the strong support of the Chinese-American community, which continues to donate substantial amounts to the garden’s development.

Hang Ping: Speaking of cultural diplomacy, how do you see the connection between Chinese gardens and their current users, particularly in the U.S. context? For instance, in Germany, gardens seem to be more about appreciating Oriental or classical culture. Has this changed in your experience with Liu Fang Yuan?

Taro Zheming: The garden is primarily for viewing, but it also serves as a cultural center. Chinese parents often bring their children here to grow up immersed in what they consider traditional Chinese culture. They also invite American friends to experience Chinese culture in the garden.

One significant difference between German and American gardens is funding. Maintaining a Chinese garden is extremely costly. In Germany, there isn’t sufficient funding or a dedicated community to support the upkeep. In contrast, the Chinese-American community here is incredibly passionate, donating generously to sustain and expand the garden.

Hang Ping: Why do you think Chinese-Americans have such strong cohesion?

Taro Zheming: My guess is that many Chinese immigrants to the U.S. came from families with substantial social and financial capital. Many were highly educated or came from banking and business backgrounds in cities like Hong Kong and Shanghai. Their integration into upper-class society allowed them to wield significant social influence, fostering a sense of community.

For instance, the first Chinese garden in the U.S. at the Met was supported in part by influential figures like I.M. Pei. This contrasts with the stereotype of Chinese immigrants as impoverished laborers, highlighting a different narrative of Chinese-American history.

Initially, his father ran a rice shop, but it wasn’t very successful, so he handed it over to Tan to manage. Tan later shifted to the canned pineapple industry and accumulated capital during the 1880s. By the early 20th century, when Britain established rubber plantations for export in Singapore, Tan had enough wealth to enter the rubber industry. Although he diversified into other ventures later on, pineapples and rubber were his two primary businesses, forming the basis of his capital.

Other significant figures included Lim Nee Soon and Lee Kong Chian, who were also giants in the pineapple and rubber industries. In Singapore, you can still see many buildings donated by Lee Kong Chian. His companies, Lee Pineapple and Lee Rubber, remain prominent family businesses in Singapore.

One interesting thing is that some memoirs from their contemporaries describe connections within these business networks. One memoir mentioned that the author’s father was a cousin of Lee Kong Chian. The father came to Singapore as a teenager and started working in one of Lee’s rubber plantations. Gradually, he began his small-scale ventures, acquired resources, and eventually leased land for pineapple and rubber cultivation, eventually transitioning to other businesses.

This illustrates how, in Singapore, these networks weren’t merely family-based—they were more like clan-based or community-based connections. People could initially anchor themselves within a shared industry and, once stable, pursue their own entrepreneurial ventures.

This is why I feel Singapore’s plantations differ from the typical colonial narrative of plantations. While labor exploitation existed, there was also a cycle of opportunity and mobility. In a foreign land, such community cohesion felt like a source of solidarity.

Singapore also built a Chinese garden as early as the 1950s, predating the overseas Chinese gardens of the 1980s mentioned by Zheming. This garden wasn’t constructed by mainland China but was instead designed by a Taiwanese architect. Later, in the 1990s, when Suzhou and Singapore became sister cities, a Suzhou-based garden company donated a bonsai garden to the existing Chinese garden. It was recently renovated and reopened during the Mid-Autumn Festival, attracting many Singaporean Chinese. This kind of collectivity, as Zheming mentioned, seems to be mirrored in Singapore.

Taro Zheming: I believe some of Lee Kong Chian’s descendants have donated gardens here in the U.S. I stumbled upon his name while researching—he stayed in the U.S. for some time during the war, and his children continued their education here. His granddaughter or great-granddaughter eventually settled in California after getting married.

Jiang Yao: If we were to forcefully categorize the development of pineapple plantations in Singapore, Lee Kong Chian came later, with larger-scale operations than Tan Kah Kee. By that time, Tan had already divested from plantations. This might be why Lee Pineapple is more enduring and well-known. However, they recently shut down their last pineapple production line due to difficulties sourcing high-quality pineapples.

When chatting with friends, many mentioned that they grew up drinking Lee Pineapple juice. So, within Singapore’s context, Lee Kong Chian holds a significant place.

Hang Ping: Listening to your accounts of gardens in the U.S. and Singapore, it strikes me that both places are immigrant societies. This contrasts sharply with the context in Germany, where integration seems more challenging. When discussing cross-cultural dynamics, I wondered if collaborations like a Chinese and a Mexican gardener working on a garden in the U.S. could open up dialogue about integration. However, in Europe, such discussions seem far less common.

Jiang Yao: What Zheming described feels more like a process of collision and regeneration within a shared space. In a previous forum, an elderly gentleman shared challenges in maintaining Chinese gardens.

In the 1980s, China gifted a garden called "Qian Garden" to Ruhr University in Germany. Maintenance has been an ongoing issue. The gentleman, a German with a passion for horticulture, lamented his lack of knowledge about traditional Chinese pruning techniques and wished for guidance from a Chinese master gardener.

In this context, issues like maintenance and authenticity come to the fore. It seems that, at least in the case of Qian Garden, there isn’t a local Chinese community to engage with or support it.

Taro Zheming: In California, authenticity isn’t a concern. As long as it looks good and serves its purpose, people are satisfied. There isn’t the same level of scrutiny about historical accuracy that a historian or art historian might bring.

Jiang Yao: I recall seeing materials on Liu Fang Yuan, highlighting technical innovations during its construction. For example, instead of traditional wooden structures, they used steel frames to ensure durability.

Taro Zheming: Yes, due to California’s earthquake regulations, wooden structures couldn’t be approved. These gardens are steel-framed but clad in wooden veneers to maintain the traditional appearance.

Hang Ping: Hearing about gardens in the U.S. and Singapore, I feel that ordinary Chinese people don’t have much of a connection to these spaces or a strong sense of belonging.

Jiang Yao: That’s true for the Chinese-American community. Liu Fang Yuan, situated in California, belongs to the American West Coast, where the cultural context differs from the East Coast.

Taro Zheming: There’s also a distinction between southern and northern gardens, much like the difference between gardens in southern and northern China.

Lin Haodong: This reminds me of a fascinating garden in Shanghai’s Yangpu District, located in a tuberculosis hospital. Its usage rate is surprisingly high, with many patients strolling there.

Taro Zheming: Speaking of usage, the gardens in old Chinese steel factories probably had the highest foot traffic. Many factories included classical-style gardens for workers to relax during lunch breaks or after shifts.

Jiang Yao: Returning to Liu Fang Yuan, I wonder if it functions more as a park. By contrast, the Met’s Chinese garden is an exhibit rather than a park.

Taro Zheming: Liu Fang Yuan serves as both a park and a cultural venue. For instance, last week, it hosted a lecture on traditional Chinese medicine, drawing a mix of Chinese and American attendees. Interestingly, the local Chinese community here seems even more committed to traditional practices like Chinese medicine compared to those in China.

Hang Ping: That reminds me of the experiential nature of Chinese medicine. In our fieldwork, we found that local doctors tailor treatments to their patients’ environments and habits. This approach feels distinct from modern medical systems and requires a long-term relationship between doctor and patient.

Taro Zheming: Traditional Chinese medicine education has shifted toward a Westernized framework, which may contribute to skepticism. However, Chinese medicine’s essence lies in its personalized approach, which modern standardized training struggles to replicate.

Hang Ping: It seems like a broader trend—seeking scientific validation for traditionally intuitive practices, whether in medicine, history, or literature.

Taro Zheming: That’s true, though cross-disciplinary studies face challenges in quantifying or comparing knowledge systems with different worldviews.

Hang Ping: Well, let’s wrap up here for today.

Yunnan Garden, located within Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, is regarded as the only remaining example of a 1950s Nanyang-style garden that integrates Chinese aesthetics. Image sourced from the internet.

PhD candidate in Landscape Architecture at the University of Toronto, Canada, and section editor for Landscape Architecture Frontiers. Currently studying in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto, his research focuses on historical theory, with particular emphasis on the history of knowledge, landscape infrastructure, cultural landscapes, and critical heritage studies.

「 Plant South Salesroom」

Established in 2021, Zhinan Men’s Department is a plant culture research and creative action team. It aims to reimagine contemporary (urban) everyday life through a plant-centric perspective by researching plant culture and organizing creative plant-related activities. Employing cross-scale and multimedia approaches, the team seeks to reshape the connections between commerce, culture, and nature.

本次圆桌分享从Rubén Montesinos的视觉研究项目《园艺指南》出发,探讨植物流动性与殖民历史的复杂关系。Rubén的项目通过研究特征、形式、物种等要素揭示园艺在城市景观中的变动性,展现其作为社会文化表达工具的作用。

圆桌讨论内容涵盖墨西哥城的园艺实践与殖民联系,菠萝等作物的全球迁徙对经济和文化的影响,以及艺术家Minerva Cuevas和Ryan Villamael如何在展览中反思植物与殖民的关系。讨论还聚焦美洲、东南亚和中国的植物流动和文化交融,尤其关注华人社群在东南亚菠萝种植园形成的独特社会关系。

此外,讨论将结合Gilles Clément的《The Garden in Motion》,通过中国的生产性景观案例,进一步探索植物的时间性与流动性,展现园艺在多元历史背景下的深远影响。

林浩东:欢迎大家来到我们的圆桌,我是龟力空间的负责人林浩东。非常高兴这次能邀请到植南门市部的杭平跟江垚,还有在加拿大的哲铭来参加我们的圆桌会议。这次圆桌内容是以我们展览的背景出发的,开始讨论前我先给大家介绍一下展览的背景。本次展览是一个关于墨西哥园艺的项目,由西班牙艺术家Rubén Montesionos拍摄。他拍摄的内容是墨西哥城街道上各种奇形怪状的灌木。此项目想要通过这些灌木为出发点去研究灌木本身以及墨西哥城有关阶级方面的内容,基于这些原因我们邀请到了植南门市部跟哲铭来参加我们的圆桌。在这里我先给大家分享一张图片作为开始的起点。

这张图片是我在做海报时偶然发现的。图片展示了路易十五儿子的一个婚礼,是一场假面主题的舞会,你可以理解为当时的一场cosplay。他们cosplay成各种奇形怪状的东西,仔细看会发现里面有人会穿着中国人、土耳其人的装扮,甚至打扮成灌木的形状。这种装扮跟此次的展览之间是有一定联系的,像有观众之前问说为什么要把那些灌木塑造成小猫小狗的形状,所以这张图片非常适合作为今天的圆桌的一个起点。

下面有请哲铭来聊聊关于墨西哥城园艺的一个具体情况。

Taro哲铭:刚才提到修剪成奇形怪状的修剪方式,其实最早在罗马时期出现,但大概16世纪以后重新在欧洲复兴起来,并且越演越烈。一开始可能只是修剪成金字塔形或球形,但最后变成了特别浮夸的修剪成螺旋形或者是各种奇形怪状的动物,甚至是人的造型。电影《剪刀手爱德华》里面有一幕是爱德华的剪刀手特别擅长修剪造型,跟剪头发差不多。这种修剪在当时的欧洲特别流行,在欧洲国家之间几乎成为一种竞争的状态,后来从法国传到了荷兰,最后又到了英国,成为了大国之间在文化上面互相竞争的文化现象,各个国家之间发展成不同的风格。我对《A Guide On Gardening》这本书感兴趣的点在于我的背景来自于景观设计与园林史,所以我也会经常去在街上拍一些这样的照片。我觉得这本书非常有意思的是,这是一个西班牙的摄影师,在墨西哥发现了这种修剪得非常欧洲的灌木。在后殖民时代,一个西班牙的摄影师重新去探索了这种殖民视角下诞生的一个城市现象。墨西哥之所以会出现这种欧洲的园艺风格的其中一个原因是,16世纪之后西班牙对于墨西哥的殖民。直到独立前的整个殖民时期,墨西哥在园艺、城市规划、还有建筑上面都很大程度地受到了西班牙的影响。如果大家有机会去墨西哥城旅游的话,会发现很多非常典型的欧洲风格花园,花园周围是修剪得很整齐的绿篱。如果是个四方形的广场的话,它可能四个角上会有修剪得比较奇形怪状的灌木作为一个锚点去固定那个角。

修剪园艺其实就跟平常修剪头发一样,需要经常修剪来保持造型,导致你要花很多的钱和时间去维持这个动物的形状。你剪了一个小猫,长时间不修剪的话,小猫就变形,看不出来是小猫。能够修剪的越多,也证明这一家人越有钱,在一定程度上也变成了大家炫耀自己经济地位或者社会地位的一种途径,算是一种变相的、低调的,炫耀自己有钱的方式。

林浩东:跟Rubén采访的过程中,你刚才前面提到的两点其实他也都提到过。通过在墨西哥城的各个街道游荡并进行拍摄,他发现,在有钱的一些街区,修剪频率会更加频繁一些,他的观察是大概两三个月要修剪一次,有钱人街区的灌木会更加整齐,(经济)稍微普通一些的街区,修剪就不会那么频繁。像哲铭提到的墨西哥城所受到的园艺风格影响,Rubén在拍这个项目时,也对此产生了一个问题,他会疑惑说,墨西哥城的这种园艺修剪风格是西班牙的殖民者来之前就有,还是来之后才有的。实际上我们在聊灌木的时候也不仅仅只在聊灌木,我们也会聊到植物,所以想请植南门市部给我们聊聊,在这种全球史视角下的植物和殖民,它们之间的一个联系或者或者一些别的相关内容。

江垚: 首先想跟大家分享植南门市部的一个长期研究项目,叫《菠萝流浪史》,之前也出过一个小册子。在后殖民的一个时期下面,会有西班牙的摄影师去到墨西哥,从摄影或者从游荡的这样一种城市观察视角去进行一种理解。包括像浩东提到的Rubén抛出来的那个问题:像这样的一个修剪,或者所谓的欧洲风格,是之前还是之后有的。在现在整个人文的大领域里面,不管是全球史的书写,还是西方对于殖民的反思,或者说殖民的批判也好,人们会去讨论动物或者植物,例如蘑菇,大家可能也知道前几年非常火的罗安清(Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing)的《末日松茸》(《末日松茸:资本主义废墟上的生活可能》),会讨论很多其他的,除了人之外的一个对象。

在这个里面会有一个小小的背景,差不多就是刚刚哲铭说到的在十六、十七世纪左右,全球物质大交换的一个时期,不只是人从一个大洲迁到另外一个大洲,人们会说至少我要带着我的种子、作物、动物;甚至是一些疾病或病毒等,它可能会随着人进行迁移。在原来的书写里面,或者说在上个世纪的书写里面,是以人类为中心的视角——是我,人,把它从远方带到了这里。物品作为人的一个附属,从这里移动到另外一个地点。然而在过去这几十年的语境里面,至少我个人的观感是整个西方反思里,人们会开始思考:如果换一个视角去看这件事情,认为不光是人把物带来带去;而反过来说,各种非人的对象,在跟着人的移动里面,会不会也会有一些自发的影响行为。

像哲铭讲到的修剪,除了去看这户人家是不是更有钱之外,其实反过来是不是也可以理解为因为你要维持它的造型,所以你反过来被这个植物驯化了。我们经常说人驯服植物,或者说人对植物进行了一种控制,但是反过来是植物也在驯化人,它要求你不断地去做这种修剪,而且你可能要有相对的修剪记忆。其实我们更感兴趣的是,不止说是人去发明创造东西,除了在人作为主体的发明和创造之外,修剪成型的灌木也让人去跟着它做一些适应。在很多全球史的书写里,当聊植物这个对象,大家会思考,把这个植物从一个地方移到另一个地方,气候环境产生变化之后,那与其相关的一些耕作方式,或者说种植维护的方式,会不会有相应的调整?或者说完全是一个创新,逼迫一些新的可能性出现?

我们之前做的关于菠萝的项目,目前全球植物学家认为的它唯一的原产地是南美的北部大部分地区。其他的地方其实都是在后期,它到了那个生长环境之后,留下,慢慢成为当地的作物。比如说,在很多新加坡的文字书写里,会认为菠萝是新加坡遍地都是、很常见的一种街头水果、一个对象,但实际上新加坡人不会说它是土产物。它是十五、十六世纪到的新加坡,然后这里的环境更适合它生长,它在这个环境里更自如,我们几百年后再去看它,它就会变成一种习惯的存在,好像就是一个土产了。因为人,很难可以活到300、400岁,在这样一个时间维度下面,你会觉得说,它就是一个在这里的东西。那如果我们真的往历史去追溯,你会发现它其实是被介绍到这里来的。

1495年哥伦布第二次大航海的时候,他到达南美跟北美相接的小岛群落,发现了菠萝这样一种水果,或者说果实,他对此感到新奇。菠萝非常高甜,在那个时候,欧洲还不完全掌握熟练制糖的技艺,但欧洲人很嗜甜,所以菠萝就会变成一个比较理想的带回去的所谓的“战利品”。据说,哥伦布把菠萝从南美带回西班牙,献给了西班牙国王,国王吃完后赞不绝口。但是那个时候还没有蒸汽船,蒸汽船大概是到了18世纪初期才有,所以那个时候的一次航海其实可能是要经过大几个月,大概三、四十天。像菠萝这样的一个高甜的水果,并不耐放,所以说法还有待考证。但目前也有的写法上面会提到哥伦布当时可能带了三、四个菠萝,回到的时候,其他都烂掉了,还剩一个好的,他就把那个好的献给了西班牙国王。

当时欧洲的自然环境下没法种出菠萝,他们可以把菠萝种下去,但是菠萝不会结果,不会有大的果实,所以很难在欧洲本土或者欧洲的领域范围之内吃到菠萝。物以稀为贵,慢慢地,在十六、十七、十八世纪,菠萝就成为了一个身份地位的象征。如果你每天可以吃到菠萝,那代表你非常富有。菠萝成为了一个炫耀的资本。甚至有记载,到了十九世纪初期的英国,中产阶级的家庭要请客吃饭或办酒食时,他们可能会花当时的一块钱去租一个菠萝,把它放在大转盘正中间,作为一种好客以及对这顿饭的重视的象征。这顿饭吃完这个菠萝就被还回去了,他们不会买下来,因为他们也舍不得吃。所以当时其实是有这种所谓的菠萝租赁服务。也有记载说,一个菠萝被购买吃掉之前,可能会经历两到三次租赁服务。

这种小的细节,或者说有点像历史里面小的趣味也好,八卦也好,园艺修剪这样的一件事情,还是说是菠萝这样非常具体的一个对象,仿佛给现在去反思这段殖民时间的历史,提供了不太一样的思路。我们再去讲全球史时,它到底是一个怎么样的全球史?在这样的一个大的语境里面的各种的词汇和语料,这些非人的对象可能会帮助我们去发掘到一些新的可能,发现我们原来从一个人为主体的对象里面去书写、去理解的时候,所容易忽略掉的,认为理所当然的一些事情吧。

林浩东:对。其实像江垚刚才提到的,我觉得非常核心的一点就是关于大家观看的视角这么一个问题。像Rubén的这个项目,如果你单纯的来看的话,你可以把它理解为殖民意义下,一个西班牙人回到墨西哥城的这么一个视角。但是如果我们单纯从他作品的角度来讲的话,项目的核心主体是图像中心的灌木,但实际上我会留意到灌木背后的一些环境。比方说,后面的一些建筑物,成为了这个项目的附加信息。灌木背后的背景反而是我觉得他这个项目真正比较有意义,或者更能够触动到我的地方,我会观察它背后的一些场景,比方说墙面上的一些缝隙被植物撑开,一些破碎的镜子,它们能够从中反映出一些更加具体的墨西哥城的本身。其实像杭平平时也会做很多的艺术实践,能不能请杭平给我们介绍一下更多关于以植物为背景或者以植物为主体的展览或创作,让我们有一种更好的视角去观看。

杭平:我对于这个项目的第一反应除了你刚刚关注的像背景的部分,拍下的那些内容以及像哲铭说到的园艺修剪的部分,我其实也关注这个项目作为一个摄影项目的本身,在进行了拍摄展览这个动作之后,呈现出来的会有什么样不一样的反应。哲铭跟江垚在聊的时候,我稍微捕捉到一个信息。他说那些园艺被修剪成小猫小狗的样子,变成一个财富的符号。我们在做《菠萝流浪史》的时候,发现它原来可以被租赁,它已经变成一个日常生活中的存在,发展到很民用的阶段。在民用阶段,普遍的社会共识又构建出这样一种财富符号或象征。这个动作其实有个特性:它都剥离了原有的自然属性。比如说,你在园林进行修剪的时候,要把它变成一个不属于它自然生长的样子,或者在培育栽培的时候,就已经做了这样的动作,让它更加适应城市的环境。

菠萝也是这样子。在谈论菠萝的时候,我们脑海中想象的是它在水果市场的样子,基本上是跟它在菠萝田的那个样子有所区别。它原来那些叶子啊什么的,我们是不去记录的,在我们的脑海印象当中是把它剥离开来的,我们脑海中印象最深的往往是已经被剥离开来的、去掉所谓的“原来的自然属性”的那个画面。我对这件事情还挺有兴趣的。我会以两个艺术展览讲一下,或者是回应一下刚才的殖民话题,以及修剪过程当中,慢慢从一个自然物变成人造物的这个过程。

杭平:这个展览是马尼拉Silverlens画廊的展览,它在马尼拉和纽约各有一个空间。展出的艺术家叫Villamael Ryan,平常做的比较多是剪纸。这个是展览的一个文本部分,来自菲律宾大学出版社主编。展览的标题叫做《Return, My Gracious Hour》,这个展览受到了诗人Jose Rizal(何塞·黎刹)的作品《Memories of My Town》的影响。Jose其实算是所谓的菲律宾的国父,他写了这么一首诗。

When I recall the days

That saw my childhood of yore

Beside the verdant shore

Of a murmuring lagoon;

When I remember the sighs

Of the breeze that on my brow

Sweet and caressing did blow

With coolness full of delight;

When I look at the lily white

Fills up with air violent

And the stormy element

On the sand doth meekly sleep;

When sweet 'toxicating scent

From the flowers I inhale

Which at the dawn they exhale

When at us it begins to peep;

I sadly recall your face,

Oh precious infancy,

That a mother lovingly

Did succeed to embellish.

I remember a simple town;

My cradle, joy and boon,

Beside the cool lagoon

The seat of all my wish.

Oh, yes! With uncertain pace

I trod your forest lands,

And on your river banks

A pleasant fun I found;

At your rustic temple I prayed

With a little boy's simple faith

And your aura's flawless breath

Filled my heart with joy profound.

Saw I God in the grandeur

Of your woods which for centuries stand;

Never did I understand

In your bosom what sorrows were;

While I gazed on your azure sky

Neither love nor tenderness

Failed me, 'cause my happiness

In the heart of nature rests there.

Tender childhood, beautiful town,

Rich fountain of happiness,

Of harmonious melodies,

That drive away my sorrow!

Return thee to my heart,

Bring back my gentle hours

As do the birds when the flow'rs

Would again begin to blow!

But, alas, adieu! E'er watch

For your peace, joy and repose,

Genius of good who kindly dispose

Of his blessings with amour;

It's for thee my fervent pray'rs,

It's for thee my constant desire

Knowledge ever to acquire

And may God keep your candour!

他基本上被认为是菲律宾国父或者民族英雄,在西班牙殖民菲律宾时期启发了民众的反抗。在菲律宾的历史当中,经历了西班牙、美国、日本的统治。西班牙是三百年,美国四十多年,然后是日本二战时期,到二十世纪四零年代的时候,菲律宾才建立自己现在的菲律宾共和国。他写的那首诗基本上描写的风景画面是他记忆当中的风景。他把风景跟家乡非常紧密地联系起来,描述着一些具体的意象,但我其实没有看到什么非常特别的东西。我站在现在这个视角下,而且我也没有经历当时他们的状态,所以我以现在的眼光去看待的时候,我其实不知道这首诗为什么会那么地打动人,但我可以放在当时的一个历史当中去进行分析。

他大概就活了35岁,在年轻的时候流亡到欧洲的法国,然后到了香港,最后被菲律宾当地的殖民政府流放到南方的棉兰老岛。这个过程当中,他确实会有对于家乡或者是对于家乡风景的一个回忆。这个风景的回忆,可能对于当时的人来说是打动人的,只是我在反复观看的这个过程当中,我想到的第一个问题是菲律宾被西班牙殖民了300年的这个过程里,为什么菲律宾还能作为一个民族或一个国家去重新把它再建构起来?它为什么会有这样子的反抗——因为菲律宾有7000多个岛屿,80多种语言。我也问过我的菲律宾朋友,他说,之前可能也是因为这种地理跟语言上的一些原因,菲律宾有300多年都没有办法形成这个国家跟民族还有文化的构建。他们把Jose当做一个民族英雄的时候,整个故事让我觉得很不可思议。他说Jose其实并没有发动最后一次的反叛,但是政府把他抓了,因为反叛的领袖是受他的影响进行发动的,所以把他给杀了。我觉得这个过程像是一种戏剧,或者像我菲律宾朋友说的是卡通式的一个过场:一个英雄倒下,另外一个英雄起来了,然后变成一个新的政府或者一个新的国家,这过程中好像没有普通民众的声音,民众是被英雄所引领的。

我在看这个展览的时候,我第一反应是不去看这个展览的文本,因为我知道在那个语境下去谈论植物的话,多多少少会有一个先入为主的感受,但我确实在展览的作品中看到了一些线索。我觉得它算是一种回应,但它不算是一种直接对于殖民的批判。整个展览作品就像刚才的视频出现那样,很多是通过剪纸或者是装置的状态去呈现的。艺术家本身对于历史很感兴趣,但展览当中用的又是美军占据菲律宾时期的档案图像,跟他引用的这首诗中Jose说的这些东西是不同时期的。我感受到这个错位好像经常发生在艺术展览当中。但如果我把资源集束的话,好像也有蛮有道理的。他用装置的动作,让这些图像覆盖在阴影当中,好像是一种历史延续下来的殖民幽灵,或者是它所产生的影响一直在延续过程当中。他有在文本当中提到,他觉得历史这件事情,不是一个结论,而是一种媒介去重新塑造过去跟现在后殖民的一些画面。当然这个是他的看法,而且这是策展人也不是艺术家本人的表达,我对这个东西还有点疑虑,但是我觉得可以。放一放,我们等会再讲。

Installation view of Feast and Famine, kurimanzutto, Mexico City, September 22–October 24, 2015

杭平:另一个我想提到的展览是一个墨西哥籍的女艺术家(Minerva Cuevas)做过的跟巧克力可可相关的展览,展览名字叫《盛宴与饥饿》(Feast and Famine)。这个展览当中,有很多用巧克力去做的雕塑,以及跟考古图案档案进行的一些结合。这个展览在墨西哥发生的,艺术家回应了一些当地的神话故事,还有殖民有关的东西。

Minerva Cuevas, Bitter Sweet - Hershey’s (detail), 2015

Minerva Cuevas, Bitter Sweet - Hershey’s (detail), 2015

杭平:举个例子好了,像这个作品,Minerva用巧克力重新画了一个关于欧洲食人族故事的图像,我觉得挺有讽刺跟幽默感的,又因为巧克力是可食用的,所以我觉得她在符号的运用上跟材料本身的文化语境处理上是比较精彩的。我当时跟艺术家有过工作室访谈,我当时的问题是:像她这么擅长运用符号的艺术家是怎样去选择这些符号的?她当时给我展示了一个影片。

看完这个影像我又有了很多问题。比如说,影片里老奶奶说松鼠来吃可可豆时,她不会感到反感,因为这也是他们生活当中的一部分。我有一个很极端的想象,比如说,当殖民者来到这个地方,从生物意义上来说也是抢夺生态位的一个过程,如果说把人跟人当做不一样的两种生物看待,那宗主国对于前殖民地的原居民来说的话,他们可能就是不一样的生物了,这样他们到来的过程跟松鼠去抢她这个可可的过程当中有什么区别吗?我当时有这样一个很极端的、很激进的问题,但这个问题我没有问出口,因为我担心艺术家会觉得很被冒犯。